I think there are three areas in particular where we need to re-imagine what our education system should be like and what its goals should be:

Skills for the Fourth Industrial Revolution. The world economy is entering what is sometimes referred to as the information age or, alternatively, the fourth industrial revolution. The first industrial revolution (starting in the 1700s) was characterized by mechanization powered by water and steam. The second was characterized by a functionally and geographically broader mechanization powered by electricity. The third industrial revolution (starting in the 1970s) was characterized by enormous advances in computational ability, data analysis, and communication – all powered by computers that grew exponentially more capable, ubiquitous data networks with cheap data storage, and new communication devices that allowed instant access around the globe. [1]

We are now on the cusp of what some are calling the fourth industrial revolution – a term popularized by Klaus Schwab, a German engineer and economist. This new economic phase is characterized by a fusion between the physical, digital and biological spheres. Think of an economy powered by combinations of artificial intelligence, nanotechnology, genetic sequencing, biotechnology, and networks containing literally millions of sensors. Value will be produced by intangibles – ideas rather than things – and change will happen at an exponential rather than linear pace. Our education system, however, has its roots in the first and second industrial revolution where the desired output was a large number of people with a common base of knowledge that could fill repetitive factory and middle-management jobs.

A recent report by the World Economic Forum tried to define a new model of education aimed at meeting the needs of this new economy. [2] It listed eight characteristics thought to be essential for advanced learning:

Global citizenship skills (e.g. awareness of other countries and cultures);

Innovation and creativity skills (e.g. complex problem solving and analytical skills);

Technology skills (e.g. programming, data analysis and digital responsibility);

Interpersonal skills (e.g. emotional intelligence, leadership and social awareness);

Personalized and self-paced learning (e.g. based on the individualized needs of each student);

Accessible and inclusive learning (e.g. a system where everyone has access to educational resources);

Problem-based and collaborative learning (e.g. requiring peer collaboration that mirrors the future of work); and

Life-long and student driven learning (e.g. encouraging everyone to continuously expand and enhance their skills).

It would be completely unfair, of course, to lay the blame for centuries of racism and classism at the feet of our educators. Even well-meaning teachers can only accomplish so much in our current education system. Fortunately, I think that the twin technologies of artificial intelligence and virtual reality have the potential to dramatically reshape the educational landscape and, in the process, dramatically level the playing field. In the past, children from affluent families went to schools that had the best facilities and the best teachers, and children from poor families made do with whatever was left. In the future, schools for the affluent will still have the best facilities but virtual reality may minimize the gap. Don’t have an actual physics lab in your school? In the future a virtual lab may be nearly as good and in some ways better. Don’t have the best instructors in person? Listening to the best instructors (who will replicate their lessons digitally) in a virtual setting may be the next best thing. This will be particularly true if the instructors you do have are supported by automation and artificial intelligence so that they can focus on teaching rather than testing, evaluations and paperwork.

Second, schools are increasingly taking on the role of “soup kitchen” by being a primary source of food for children from disadvantaged families. In a normal year, close to 30 million kids get either a free or reduced-cost lunch at school. Smaller programs for breakfast, snacks and summer meals also exist. [4] Schools took on this responsibility primarily to improve school performance (it turns out that hungry kids don’t learn well) but it helped that the federal government was willing to fund most of the cost. It would not surprise me if this role expands in the future so that school kitchens end up providing breakfast, lunch and dinner to students, and perhaps to other family members as well.

Third, I think it is almost inevitable that schools will become providers of health and social services, including services to both children and parents. Routine wellness exams, simple health prescriptions, or the detection of child abuse, domestic violence, or illegal drug use (and the appropriate social interventions) may become common school services – or at least services that other agencies administer on school grounds. School districts, particularly in urban areas, find themselves sucked into these issues already, they just don’t have the tools to respond effectively.

In the future, each child is likely to have a digital companion or “avatar” to help guide them through their individualized study plan and these avatars may become confidants that students share personal problems with. In addition, schools are likely to be packed with sensors that can, among other things, detect illness or injury. This all may seem a bit too “big brother-ish” for many, but if we are serious about enabling all children to reach their potential, then these are problems that can’t be ignored.

Imagining New Possibilities

The remainder of this post is going to be a “thought exercise” – more an exploration of what might be possible rather than a prediction of what is most likely. In a departure from the previous posts in this series, I’m going to be looking at least 10 to 15 years out. Partly this is because artificial intelligence and virtual reality need more time to mature and to build out the necessary content. But it is also because I think the educational establishment needs a “changing of the guard” to teachers and administrators raised in the internet age. Technological change is hard unless there is a true understanding of what is possible and a commitment to making it work. And in keeping with the theme of all my posts, I will end with a discussion of how all of this will affect midwestern cities.

Educators have long known that different students learn in different ways. Competitive personalities might learn best through games, while others might learn best through stories, or hands-on problem solving. Resources limitations, however, have pretty much dictated a one-size-fits-all approach. Is it any wonder that students who don’t fit a particular teaching style struggle to master the content, get frustrated and start thinking of themselves as slow learners? Even students who learn quickly get bored when the teacher has to adjust the pace of the class to those who are falling behind. The result is that the fun of learning evaporates, natural curiosity is squashed, and students disengage from the classroom.

It is possible that the combination of artificial intelligence (AI) and virtual reality (VR) can address all of these issues, and do it at a cost that nearly every district can afford. AI systems can already beat grandmasters at chess and VR games draw people into fantasy worlds that are so engaging that it is sometimes difficult to draw them back to actual reality. And as good as these systems are now, their exponential rate of improvement means that in just 5 or 10 years they will be hundreds of times better. Think of how good virtual assistants such as Alexa or Siri are at answering your questions, reminding you of your appointments, or giving you the weather forecast. Now imagine them with capabilities and “intelligence” multiplied by 100 or 1,000. Or ponder the consensus projections for the virtual reality gaming market – expected to grow at a compounded annual rate of over 30 percent for the next 5 years.

In fact, virtual reality gaming is likely to be the technical foundation on which much educational software is built. Students are likely to spend much of their day wearing virtual reality headsets that will provide them with a customized array of educational stories, games and interactive worlds to explore. Each student is likely to have their own guide for this educational experience that they can interact with throughout the day. This guide, or avatar, will be powered by artificial intelligence but directed by each student’s teacher so that the avatar leads the student through the correct learning and skill-building activities. The advantage of this approach is that the specific stories, games or lessons that each student receives can be customized to match their interests, learning style, and current skill level. All the students in the class may be learning about multiplication, but each student’s experience may be quite different. [5]

Source: VAR360.com

The VR headsets will not only allow the students to see and hear the material they are learning, but will contain multiple sensors to track the student’s response or actions (e.g. tracking finger and hand motions that allow an answer to be selected from a list, or a word typed on a virtual keyboard, or an airplane to be flown through an imaginary world). In addition, artificial intelligence systems are getting so good at natural language processing that students will be able to interact verbally if that is appropriate. For example, students are likely to simply talk with their avatar throughout the day as they discuss the last activity they completed or the next one in the queue.

The result will be that the system will not only be presenting information but constantly gathering information based on the student’s actions – did the response indicate an understanding of the material? Is the student fully engaged with the activity? Is a personal intervention by the teacher needed? This information will allow the system to constantly adjust the next activity – perhaps a harder version of the same educational game for students ready for a challenge, or a completely new activity for students who need a change of pace.

Despite all this emphasis on electronic learning, teachers will still play a pivotal role. Freed by automation from doing many of the grading, evaluation and administrative tasks that consume their time today, teachers will be able to spend more time actually teaching. They may be less likely to be the main presenter of information but more likely to spend time tutoring, mentoring and motivating students. There will also be a considerable portion of the day spent in “actual reality” in addition to virtual reality. Students will still need time for group projects, discussions, and traditional physical activities such as art projects, exercise or traditional games.

Although the shift to learning powered by artificial intelligence and virtual reality will require major adjustments in our educational system, I think an equally disruptive change will be what I think is an inevitable shift to all-day, year-round school. While there are likely to be educational benefits from having kids in school for more hours each year (e.g. the end of the dreaded “summer slide”), the main impetus is likely to be from working parents who simply want to be sure that their children are safe and well cared for while they are working. Even during the occasional school breaks, school buildings may remain open (albeit without teachers) simply to provide daycare and recreational services.

The flip side of this change, however, will be a significant increase in attendance flexibility. Since learning will be far more self-paced, it will be much easier for parents to arrange for their children to be out of school for music lessons, sporting events or even family vacations. And lest anyone think that year-round school would be torture for the kids, remember that the goal of self-paced, game-based, exploratory learning is to make school fun and engaging. Plus, more time in school means that there will be more time for extracurricular activities where kids can self-select things that pique their curiosity or give them more time with their friends.

Finally, all-day school will probably lead to the demise of traditional homework, perhaps aside from the suggestion to read each night. Absent the cloud of homework hanging over their heads, students will be able to spend evenings with family or friends, hopefully enabling them to be recharged for the next school day. The same applies to teachers, freed from the drudgery of grading homework. It will also lessen the impact of the “digital divide” since students will not necessarily need internet access at home.

All-day, year-round school will also necessitate three substantial changes to traditional school buildings in support of the concept that education requires a more holistic approach to the well-being of each student. To begin with, sensors throughout the school property will track every person using facial recognition technology to ensure everyone’s physical safety. Teachers, administrators and security staff will know the location of every student and every visitor, thus simplifying attendance tracking and reducing security concerns. Sensors will also be able to do basic health assessments (e.g. identifying children with a fever) which will enable teachers to quickly send students to the school clinic before illness spreads. That clinic – a second change to the school building and a far cry from the traditional nurse’s office – will be able to do simple diagnostic tests (e.g. strep throat) and administer basic treatment steps so that when children are picked up by their parents they will be accompanied by a clear recommendation for on-going care. The sensors and intelligence built into the VR headsets are also likely to enable early diagnosis of issues such as dyslexia, vision problems, or attention deficit disorder.

The third probable change will be the expansion of the kitchen/cafeteria. Although many schools already provide breakfast, lunch and snacks to many of their students, I think it is highly likely that neighborhood schools will be a major conduit for Federal programs designed to make sure no one goes hungry. This means that school kitchens will go beyond feeding just kids to being a source of food for entire families. Just as meal preparation services such as Freshly, Blue Apron, and Hello Fresh are popular with busy millennials, the same concept could be applied to pre-prepped dinners ready for parents to pick up along with their children. Government concerns over poor nutrition and childhood obesity will likely lead to an emphasis on fresh, locally sourced food, perhaps even grown on-site using hydroponics and urban farming innovations. In short, school kitchens may become the response to concerns about “food deserts” in low-income neighborhoods, and may play a key role in improving the nutritional value of meals throughout the community.

Urban Impacts

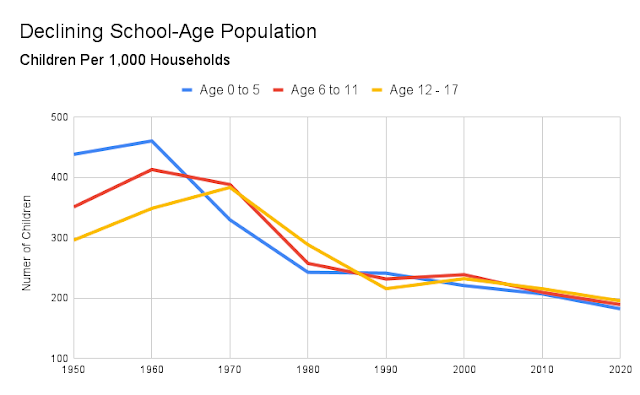

Decades ago when I first started in the urban planning profession, a common template for suburban development was a neighborhood roughly a square mile in area, with an elementary school at the center. Back in the 1970s, that approach would have yielded approximately 500 elementary aged students – roughly the capacity of a typical school. Now, the same number of households would produce about half that many students, which explains why so many school districts in older areas have had to close so many school buildings.

|

| Source: U.S. Census Bureau |

If my vision of the elementary school as a hub for not only education, but also nutritional, health and social services is correct, then it wouldn’t surprise me if schools got even bigger in order to provide economies of scale for such a wide spectrum of services. That means that schools will be much further apart than they were 50 years ago, or even today. This, in turn, means that having kids walk or bike to school will remain a rarity. Urban designer Victor Dover asked a group of adults three questions about walking/biking to school and here are the results:

Did your parents walk/bike to school? (yes = 86%, no = 14%)

Did you walk/bike to school? (yes = 61%, no = 39%)

Do your kids walk/bike to school? (yes=10%, no = 90%)

Here is his conclusion: “Children used to regularly walk to school, which gave them exercise, independence, and a connection to their community. Now they are almost always driven, partly because our communities are not designed to be walkable, on a human scale.” [6] Unfortunately, I don’t see that changing in the future, although hopefully there will be new transportation options that don’t involve the hugely inefficient process of hundreds of parents dropping off one or two children each morning and picking them up in the afternoon.

The result will be that the relationship between an elementary school and the broader community will be different than it has been in the past. Historically, schools were one of the few non-residential land uses that was allowed to be in the middle of a residential neighborhood. Seventy years ago, a school would be located on 4 or 5 acres of land, have just enough parking for the 40 or 45 staff members, and be used almost exclusively during daylight hours. It was common for schools to be directly adjacent to single family homes.

In the future, elementary schools and the associated service providers may need 12 to 15 acres of land, contain a staff of 75 to 100, need parking lots and drop-off areas that consume a quarter of the site, and be in use one way or another from 7 AM to 10 PM. Most single family homeowners will want to be at least a couple of blocks away from a use that is more akin to a commercial facility than one that belongs in a quiet neighborhood.

I would love to predict that the schools of the future will be small, neighborhood-level facilities within a 5-minute walk of every child, I just don’t see our society moving in that direction. The problem for many cities may be that virtually none of their stock of school properties will meet the needs that I have outlined. Will schools buy up an adjacent block of houses so they can expand, or will they simply close obsolete schools so they can relocate to larger, more commercialized sites? Either way will be a painful community transition.

The bottom line is that artificial intelligence and virtual reality hold the promise of dramatically expanding opportunities for academic success. The promise of an educational meritocracy for disadvantaged families may not ever be fully realized, but we may be able to get close enough to restore hope and to build a workforce that will be able to meet the challenges of a rapidly changing economy. That technological advancement, however, is likely to be accompanied by a broad and coordinated expansion of social services from both state and federal levels. Some will see this as a positive, others as a negative. In any case, if my vision for the future of education is reasonably accurate, this will be another source of community change that people will struggle to come to grips with and another force altering the physical form of cities.

Thoughts? As always, share your thoughts and ideas by leaving a comment below or sending me an email at doug@midwesturbanism.com. Want to be notified whenever I add a new posting? Send me an email with your name and email address.

Notes:

Elizabeth Schulze; “Everything You Need to Know About the Fourth Industrial Revolution”; January 2019; CNBC; https://www.cnbc.com/2019/01/16/fourth-industrial-revolution-explained-davos-2019.html

World Economic Forum; “Schools of the Future”; January 2020; https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Schools_of_the_Future_Report_2019.pdf

Melinda Anderson; “Why the Myth of Meritocracy Hurts Kids of Color”; July 2017; The Atlantic; https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2017/07/internalizing-the-myth-of-meritocracy/535035/

Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture; “Child Nutrition Programs”; https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/child-nutrition-programs/national-school-lunch-program/

Kai-Fu Lee and Chen Quifan; AI 2014, Ten Visions for our Future; 2021; Penguin Random House, LLC.

Robert Steuteville; “Walking to school, three generations”; Public Square: a CNU Journal; March 2019; https://www.cnu.org/publicsquare/2019/03/01/walking-school-three-generations

No comments:

Post a Comment