Surely you’ve noticed: Rush hour traffic is different now than it was before the pandemic.

People have theories about the underlying causes and what happens next, but few seem to have taken a deep dive into data that could give a reasonably precise understanding of what is really going on. That makes it difficult to make meaningful adjustments to transportation policy, because the safe play for city planners and transportation officials is to fall back onto what they knew before the pandemic with the assumption that eventually things will return to normal.

|

| Kansas City Traffic - 8 a.m. on a Monday |

This article will focus on high-level vehicular patterns, but there are other related issues that I will address in later posts. I will also focus on Kansas City, because it is the urban area I know best, but I will bring in data from Indianapolis and Chicago for comparisons and to underscore certain conclusions.

An Analysis With Big Data

Much of the data that I’m going to be using comes from Replica (www.replicahq.com), a company that builds large-scale models of mobility activity to better understand how, why, when and where people move around. Replica data is used by transportation officials across the country to improve their understanding of what is really happening as people move from place to place. This helps taxpayer money be spent more efficiently to get people where they need to go safely and on time. By comparison, traditional data sources are crude, incomplete and often out of date.

So how does Replica work? To begin with, Replica gathers massive amounts of de-identified data from three primary source types: public use demographic data (e.g. Census Bureau surveys of population, income and household characteristics), proprietary data from commercial sources (e.g. locational data from GPS-enabled systems or transactional data from credit card systems), and field observation data from public agencies (e.g. traffic counts or transit boardings and departures). From this data, a “synthetic population” is created that mimics the activities and movements of residents, visitors and commercial vehicle fleets for a typical weekday and weekend day in a given season. For this article, I will be using weekday data from the Fall of 2019 and the Spring of 2021 (supplemented by more recent data from other sources).

Replica data faces limitations from data sampling, the impacts of data privacy rules, and the simplifications and assumptions needed to build such a massive data model. Still, it is far more accurate, detailed and inclusive than any alternative product I know.

COVID, Work-From-Home and More

The COVID-19 pandemic was a massive disrupter for urban areas around the world, and the ripple effects are likely to be with us for years. It is important to point out, however, that the changes we are dealing with now were amplified and accelerated by technological and societal trends that have nothing to do with the COVID virus. Here are four trends that should be kept in mind:

- The shutdowns of many businesses, schools and institutions slashed the number of trips of all types and for all purposes. Transportation facilities everywhere were almost empty as people canceled anything that wasn’t essential. Commuting habits changed, and the use of online shopping and home delivery services soared.

The work-from-home trend, which had been growing slowly before the pandemic, absolutely exploded during the pandemic. Workers tried it as a way to stay employed and businesses encouraged it as a way to stay in business. Many workers liked the time they reclaimed from commuting and the extra flexibility it gave their daily schedules. Even as business locations have reopened and workers have forgotten their fear of public spaces, the percentage of office workers actually in the office is still at historically low levels. Recent surveys have indicated that 90 percent of companies allow office workers to have some type of hybrid or remote work schedule. The average number of days that workers are allowed to work remotely is 2.3, but that likely understates reality since many companies are not actively enforcing their stated policies. [2]

Transit ridership in major cities all over the country – including Kansas City, Indianapolis and Chicago – plummeted during the pandemic and is still well below pre-pandemic levels. Problems multiplied as the pandemic dragged on and transit workers either fell ill or decided that the risk of coming to work was too great. Many systems were so short-staffed that routes had to be cut which hurt ridership even more.

The labor force has been shrinking for the past few years and took a big drop during the pandemic. The labor force participation rate is now just over 62 percent, down a full percentage point from the fall of 2019. That equates to 1.6 million workers who are no longer interested in working full time. On top of that, many workers have shifted from traditional employment to freelance work in what is known as the “gig economy” [3] and many others simply changed jobs for the sake of greater flexibility in their work schedules.

The net effect is that fewer people are making the traditional commute to work now than just a few years ago. And despite the recent rants against work-from-home by some high-profile CEOs like Elon Musk and Jamie Dimon, traditional office work five days a week seems unlikely to become the norm that it once was. A recent poll of major employers in Manhattan showed that less than 40 percent of office workers are actually in the office on a typical day and less than 10 percent are in the office five days a week. [4] In the Midwest those numbers are likely much higher, but still well below historical averages. Consequently, many companies in cities across the country are down-sizing their office footprints in recognition of this new work reality.

The Impact on Traffic

In Kansas City, the estimated number of vehicular trips for a typical weekday [5] fell by approximately 5 percent from the fall of 2019 to the spring of 2021. During the morning rush hour, however, the decline was roughly 15 percent for both the peak hour (7 a.m. to 8 a.m.) and for the broader morning commute period of 6 a.m. to 9 a.m. The drop in trips to work was responsible for nearly all of that decline – falling from 45.2% of trips during morning commute hours in 2019 to only 37.7% in 2021.

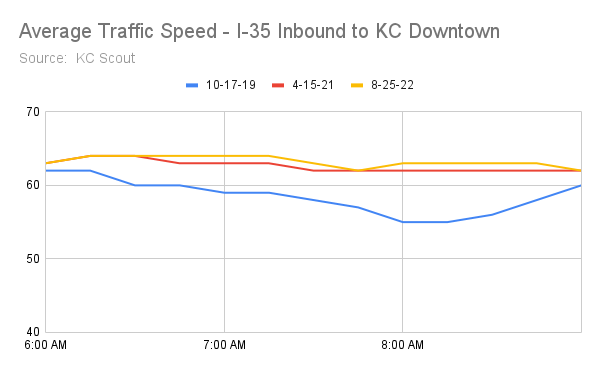

The effect of these morning rush hour reductions is predictable – congestion has been noticeably reduced. Kansas City has a traffic flow monitoring system known as Scout that tracks traffic volume and speed on major highways around the metro. [6] To double check what the Replica data was suggesting, I looked at Scout data for two different locations and three different dates. The three dates were Thursdays in October of 2019, April of 2021 and August of 2022. The two locations were both highways leading into Kansas City’s downtown loop that used to be routinely congested during the morning rush hour (neither has been widened during this time period).

At the site where I checked average travel speeds, traffic in both the spring of ‘21 and the summer of ‘22 averaged 12 to 15 percent higher speeds than in 2019 during the morning rush hour. In both ‘21 and ‘22, vehicles were traveling near the posted speed limit throughout the 6 a.m. to 9 a.m. period.

At the site where I focused on traffic volume, morning rush hour volumes were down 20 to 25 percent in April of 2021 and still down roughly 18 percent in August of 2022 compared with October of 2019.

Of course Kansas City’s downtown loop, like many downtown areas, is heavily biased toward office jobs where work from home is possible for many workers. So seeing a drop in the morning rush traffic in-bound to the downtown loop is not surprising. In fact, when I isolated just the downtown’s Census block groups as the trip destination in the Replica model, total trips between 6 a.m. and 9 a.m. dropped by 40 percent in 2021 compared with 2019. Work-specific trips dropped even more. Traffic near industrial or retail districts might be less affected, although work-from-home is widespread enough that I think rush hour congestion has declined just about everywhere.

The Evening Rush Hour is Different

In contrast to the morning rush hour, evening rush hour volumes are nearly back to pre-pandemic levels. For both the peak hour (4 to 5 p.m.) and the evening rush period (3 to 6 p.m.), vehicular traffic volumes in the spring of 2021 were only 3 to 4 percent below the fall of 2019. What is different is the nature of those trips. Traditionally, the evening rush is dominated by workers on their way home, although other trip purposes have always made the evening rush less focused than the morning rush. But now, the diversity of trip purposes has grown noticeably.

In 2019, the proportion of trips with “Home” as the destination was 43.0%, and the combination of secondary trip purposes – Shopping, Errands, Social, Eating and Recreation – was roughly equal at 43.8%. In 2021, home bound trips dropped to 39.7% and the combination of Shopping, Errands, Social, Eating and Recreation jumped to 49.2%. As you might expect from this shift in trip purpose, both average and median trip length has fallen.

The KC Scout data for out-bound trips from the downtown loop during the evening rush period was consistent with the data from Replica. I used the same locations as for the morning rush – limited access highways just outside the downtown loop – except I looked at the side with predominantly out-bound traffic. The segment that I checked for average vehicle speed showed that speeds in April of 2021 were 6 to 8 miles per hour faster than in October of 2019, although that difference had declined slightly by August of 2022.

The out-bound point that I chose for a comparison of traffic volumes showed a roughly 14 percent reduction in 2021 compared with 2019. That difference, however, shrank to approximately 6 percent by August of 2022.

I suspect that the shift in trip purpose has caused a corresponding shift in traffic away from traditional commuter routes onto more localized thoroughfares where retail shops and services, bars, restaurants and similar destinations tend to be located. Thus, even though evening traffic volumes are still down, there may be selected locations where the evening rush hour traffic actually seems worse. I also suspect that this growth in secondary trip purposes is largely powered by the work-from-home set that is taking advantage of their flexible work schedules to do things during the afternoon that they previously would have deferred until later in the evening or the weekend.

Indianapolis

The Kansas City and Indianapolis metro areas are similar in many respects, including the way that traffic patterns have changed over the past couple of years. Total vehicular trips fell by 6 percent, and trips during the morning rush period fell by 11 percent. During the evening rush period, total vehicular trips were down by a little over 3 percent. The evening rush had the same type of change in trip purpose as in Kansas City, with trips Home falling by 2.5 percent and trips for Shopping, Errands, Social, Eating and Recreation increasing by 5 percent. Finally, trips into the downtown area during the morning rush fell by over 40 percent between the fall of 2019 and the spring of 2021.

Chicago

It is one thing for two mid-sized metro areas like Kansas City and Indianapolis to have similar traffic changes, but what about a much larger metro area like Chicago? It turns out that things aren’t much different there either. Using the same Replica data and filter definitions, total vehicular trips are down by 5 percent from 2019 to 2021. Morning rush period trips are down 18 percent, but the evening rush period has bounced back so that trip volumes are roughly equal in the two periods. Again, however, the evening rush shows a more diversified array of trip purposes. Between 3 p.m. and 6 p.m., the proportion of trips Home dropped from 43.5 percent of all trips to 40.8 percent. At the same time, the secondary trip types of Shopping, Errands, Social, Eating and Recreation grew from a combined percentage of 45.1 to 50.1 percent. As with the other two metro areas, vehicular trips into the downtown area during the morning rush fell by nearly 40 percent.

Conclusions

So what does it all mean? Long-term predictions are tricky because there are multiple forces pulling traffic patterns in multiple directions. It is almost impossible to know which forces will become dominant and which will fade into obscurity. I am fairly confident, however, that going back to the way things were is not very likely.

In the short run, I think the morning rush hours will continue to be less congested than normal, but that traffic levels in the middle of the day and during the evening rush will slowly return to pre-pandemic levels. The nature of those trips, however, will continue to be more diversified with “errand” types of trips making up for a continued dip in trips from work to home. This means that while congestion may return, the location of the congestion might well shift.

More and more companies will begin to pressure employees to work more regular hours in the office. Some will push for five days a week, but most will accept some hybrid solution averaging somewhere between two and three days each week. Younger employees, in particular, will push hard for the flexibility and focus that work-from-home allows. Companies that want to attract the best talent will be hard pressed to refuse. In addition, many companies have already downsized their office footprint and are realizing significant savings. I can’t see them reversing course any time soon. In the end, I think the number of white-collar workers back in the office will rise slowly, but it will plateau at some point significantly below pre-pandemic levels.

On the other hand, labor force participation rates are showing signs of bouncing back toward previous levels as the effects of the pandemic pay-outs wind down and fears of serious COVID infections fade from memory. Growth in the number of jobs is currently strong and seems likely to remain that way absent a major recession. That means there will be more people with jobs to commute to.

The strength of the work-from-home trend suggests that rush-hour traffic should remain significantly less congested than before the pandemic, even if job growth stays strong. The wild card, however, is transit utilization. In cities with historically low transit ridership (such as Kansas City and Indianapolis), the impact will be muted. In cities where transit has historically played a more important role (such as Chicago and New York City), the impact is much more serious. During the height of the pandemic, someone who had to work could logically have switched from transit to a private car. It would have seemed safer from a COVID standpoint and the highways were so empty that there would have been little if any time penalty. But as people return to the workplace, transit needs to rebound to something close to previous levels or congestion could skyrocket.

Finally, it is important to remember that human behavior is difficult to predict in a complex system (like urban transportation). People will adjust when they travel, how they travel, and the route they take based upon the perceived ease of different transportation options. This is the force behind “induced demand” – the often misunderstood phenomenon of traffic volumes increasing when a road is widened to the point where congestion is nearly as bad as before. I suspect that reduced congestion now will entice people to drive more in the future, but I have no clue exactly how that will play out.

In the end, I think transportation planners need to reconsider upcoming expansion plans in light of the new rush hour reality created by the reduced number of office workers and by the increase in midday trips for a variety of non-work purposes. Once proposed, road projects (and transit projects) tend to have their own momentum that can move them forward even when they no longer make sense. For the sake of our cities and the people who live in them, we need to rethink our priorities.

Notes:

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; August, 2022; https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#datatracker-home.

2. Jena McGregor; “Just 4% of Employers are Making Everyone Return to the Office Full Time, Survey Finds”; Forbes; May 2022;

3. Velocity Global; “44 Eye-Opening Gig Economy Statistics for 2022”; May 2022; https://velocityglobal.com/blog/gig-economy-statistics/#:~:text=The%20gig%20economy%20is%20large,via%20an%20online%20gig%20platform.

4. The Partnership for New York City; “Return to Office Survey Results”; May 2022; https://pfnyc.org/research/return-to-office-survey-results-may-2022/

5. Source: Replica, Inc. The model was filtered to show trips that both originated and ended in the 8-county Kansas City metro area (i.e. excluding pass-through trips) and to show only trips by private auto, commercial freight vehicles, and taxi/TNC trips (i.e. excluding trips as a passenger, or trips via transit, biking or walking). Similar filters were used for Indianapolis and Chicago.

6. The KC Scout system is operated by the Missouri Department of Transportation and is based on dozens of speed and volume sensors located on major highways throughout the Kansas City Region. http://www.kcscout.com/Default.aspx